-

Author

Ye Lee -

PI

Victoria L. Tseng

-

Co-Author

Ken Kitayama, Thomas J. Avallone, Fei Yu, Joseph Caprioli, Anne L. Coleman

-

Title

Associations between Niacin Intake and Glaucoma in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

-

Program

STTP

-

Other Program (if not listed above)

-

Abstract

Background: Glaucoma is the second leading cause of global blindness [1] and is the leading cause of blindness in African Americans in the United States [2]. Patients with glaucoma exhibit damage to the optic nerve and retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), leading to visual impairment and eventual blindness if their glaucoma is left untreated. An exact etiology of glaucoma has not been developed, although its associations with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), microvascular deficiency, systemic autonomic dysfunction, and mutations in the myocilin gene have been described [3, 4].

Niacin, otherwise known as nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, or vitamin B3, is a crucial nutrient that is converted to nicotinamide adenine nucleotide (NAD) and used to mediate oxidation-reduction reactions that extract energy from dietary macromolecules. Niacin is found in meat and, to a lesser extent, in nuts, legumes, and grains [5]. In mouse models, it has been shown that not only do RGCs in the setting of glaucoma show signs of oxidative damage, namely a decrease in mitochondrial NAD and glutathione, but also that administration of niacin can slow mitochondrial dysfunction and lessen optic nerve damage. In fact, high doses of niacin (2000 mg/kg per day) resulted in no optic nerve damage in 93% of treated eyes [6].

In humans it has been shown that niacin is associated with vessel dilation and improved blood flow [7]. Additionally, Jung et al. use South Korean national survey data to demonstrate an association between niacin intake and glaucoma risk, independent of IOP [8]. This project will continue to examine the relationship between niacin and glaucoma risk, specifically within the U.S. adult population.

The study population comes from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which is a comprehensive biannual survey that is conducted and published as public use data by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [9]. This cross-sectional study focuses on the two surveys conducted between 2005-2008.

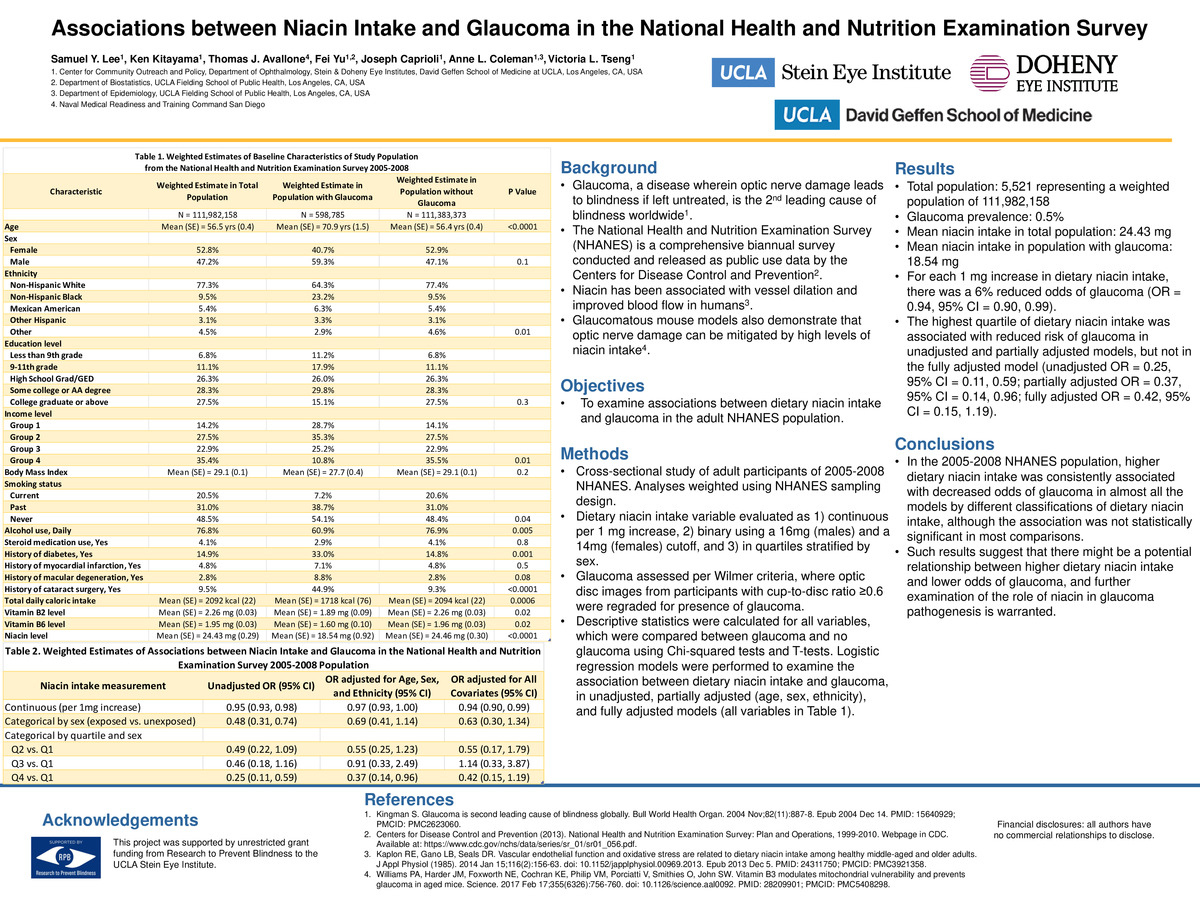

Methods: The study population included adult participants of the 2005-2008 NHANES. Dietary intake of niacin was analyzed 1) as a continuous variable per 1 mg increase, 2) as a categorical variable with a cutoff point of 16 mg per day for male participants and at 14 mg per day for female participants representing NIH recommended daily allowances [10], and finally 3) as quartiles stratified by sex. Glaucoma was evaluated according to the Wilmer criteria, where graders selected optic disc images with cup-to-disc ratio ≥0.6 and regraded them as having “no, possible, probable, definite” glaucoma, or unable to grade. Covariates included age, gender, ethnicity, level of education, income, BMI, smoking status, level of intake of alcohol, steroids, calories, vitamin B2, and vitamin B6, and whether the participant had a history of diabetes mellitus, cataract extraction surgery, macular degeneration, or a myocardial infarction. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables, which were compared between glaucoma and no glaucoma using Chi-squared tests and T-tests. Logistic regression modeling was used to examine the associations between niacin intake and glaucoma in the study population, adjusting for no, some (age, sex, ethnicity), or all study covariates. Analyses were weighted using NHANES multistage sampling design.

Results: The study population included 5,521 participants, which represents a weighted 111,982,158 US population. Among them, 56 had glaucoma, representing a weighted population of 598,784. For each 1 mg increase of dietary niacin intake there was a 6% reduced odds of glaucoma (OR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.90, 0.99). Also, the highest quartile of dietary niacin intake was associated with reduced risk of glaucoma in unadjusted and partially adjusted, but not fully adjusted models (unadjusted OR = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.59; partially adjusted OR = 0.37, 95% CI = 0.14, 0.96; fully adjusted OR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.15, 1.19).

Conclusions: In the 2005-2008 NHANES population, higher levels of dietary niacin intake were consistently associated with decreased odds of glaucoma in most models, although this association was not statistically significant in most comparisons. This suggests that a potential relationship between higher niacin intake and lower odds of glaucoma may exist, and that further investigation of the role of niacin in glaucoma pathogenesis is warranted.

Sources:

1. Kingman S. Glaucoma is second leading cause of blindness globally. Bull World Health Organ. 2004 Nov;82(11):887-8. Epub 2004 Dec 14. PMID: 15640929; PMCID: PMC2623060.

2. Sommer A, Tielsch JM, Katz J, Quigley HA, Gottsch JD, Javitt JC, Martone JF, Royall RM, Witt KA, Ezrine S. Racial differences in the cause-specific prevalence of blindness in east Baltimore. N Engl J Med. 1991 Nov 14;325(20):1412-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111143252004. PMID: 1922252.

3. Kwon YH, Fingert JH, Kuehn MH, Alward WL. Primary open-angle glaucoma. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 12;360(11):1113-24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804630. PMID: 19279343; PMCID: PMC3700399.

4. Wierzbowska J, Wierzbowski R, Stankiewicz A, Siesky B, Harris A. Cardiac autonomic dysfunction in patients with normal tension glaucoma: 24-h heart rate and blood pressure variability analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012 May;96(5):624-8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300945. Epub 2012 Mar 7. PMID: 22399689.

5. National Institutes of Health (2020). Niacin. Webpage in NIH. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Niacin-HealthProfessional/ [Accessed 13 Jan. 2021].

6. Williams PA, Harder JM, Foxworth NE, Cochran KE, Philip VM, Porciatti V, Smithies O, John SW. Vitamin B3 modulates mitochondrial vulnerability and prevents glaucoma in aged mice. Science. 2017 Feb 17;355(6326):756-760. doi: 10.1126/science.aal0092. PMID: 28209901; PMCID: PMC5408298.

7. Kaplon RE, Gano LB, Seals DR. Vascular endothelial function and oxidative stress are related to dietary niacin intake among healthy middle-aged and older adults. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014 Jan 15;116(2):156-63. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00969.2013. Epub 2013 Dec 5. PMID: 24311750; PMCID: PMC3921358.

8. Jung KI, Kim YC, Park CK. Dietary Niacin and Open-Angle Glaucoma: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients. 2018 Mar 22;10(4):387. doi: 10.3390/nu10040387. PMID: 29565276; PMCID: PMC5946172.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Plan and Operations, 1999-2010. Webpage in CDC. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_056.pdf.

10. National Institutes of Health (2020). Niacin. Webpage in NIH. Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Niacin-HealthProfessional/ -

PDF

-

Zoom

https://uclahs.zoom.us/j/94188046991?pwd=bEMxQVZ3QWVGcFcvdHNFYm5zNFMrQT09