-

Author

Haia Chakoukani -

Co-author

-

Title

Recognizing and Rectifying Dermatologic Health Disparities in People of Color

-

Abstract

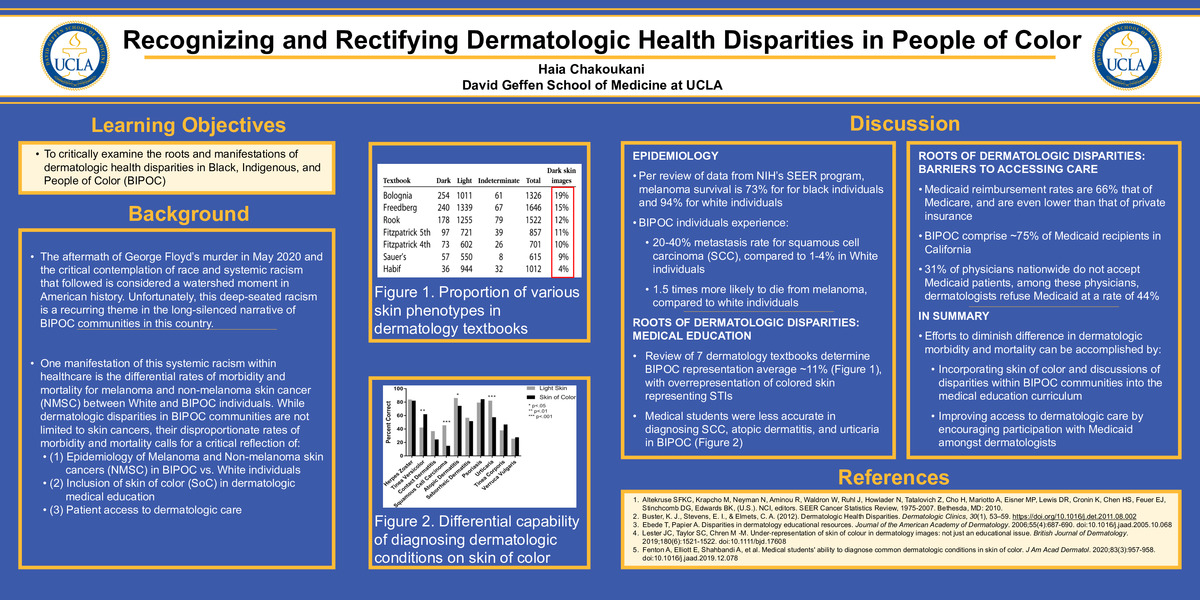

PURPOSE: To critically examine the roots and manifestations of dermatologic health disparities in Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).

SUMMARY: The aftermath of George Floyd’s murder in May 2020 and the critical contemplation of race and systemic racism that followed is considered a watershed moment in American history. Unfortunately, this deep-seated racism is a recurring theme in the long-silenced narrative of BIPOC communities in this country. A manifestation of this systemic racism within healthcare is the differential rates of morbidity and mortality for melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) between White and BIPOC individuals. While dermatologic disparities in BIPOC communities are not limited to skin cancers, their disproportionate rates of morbidity and mortality calls for a critical reflection of (1) patient access to dermatologic care (2) inclusion of skin of color (SoC) in dermatologic medical education, as well as (3) the lack of pigmented skin in dermatologic research.

CONCLUSION: Dermatologic health disparities between White individuals and BIPOC are indeed multifactorial. While the detection of melanotic lesions on SoC poses a challenge to diagnosis, it is far from adequately explaining the current disparity in dermatologic care that exists in communities of color. BIPOC patient access to dermatologic care is stifled by a shortage of dermatologists of color and a narrow Medi-Cal acceptance rate by dermatologists. Examination of dermatologic medical education textbooks reveals a paucity of dermatologic conditions represented on pigmented skin, with a problematic overrepresentation of pigmented skin for venereal diseases. Additionally, dermatologic research still lags in adequately recruiting and representing BIPOC. It is the responsibility of medical education institutions to recognize and rectify these disparities by: emphasizing dermatologic disparities, incorporating pigmented skin into the medical education curriculum, and on a systems level, increasing training of BIPOC dermatologists and the acceptance of under-insured patients.

REFERENCES:

1. Adamson AS, Smith A. Machine Learning and Health Care Disparities in Dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(11):1247–1248. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.2348

2. Altekruse SFKC, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Cronin K, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK, (U.S.). NCI, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2007. Bethesda, MD: 2010.

3. Buster, K. J., Stevens, E. I., & Elmets, C. A. (2012). Dermatologic Health Disparities. Dermatologic Clinics, 30(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2011.08.002

4. Ebede T, Papier A. Disparities in dermatology educational resources. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006;55(4):687-690. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.068

5. Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students' ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):957-958. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078

6. Haenssle HA, Fink C, Schneiderbauer R. Man against machine: diagnostic performance of a deep learning convolutional neural network for dermoscopic melanoma recognition in comparison to 58 dermatologists. Ann Oncol. 2018 Aug 1;29(8):1836-1842. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy166. PMID: 29846502.

7. Lester JC, Taylor SC, Chren M ‐M. Under‐representation of skin of colour in dermatology images: not just an educational issue. British Journal of Dermatology. 2019;180(6):1521-1522. doi:10.1111/bjd.17608

8. Medicaid Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-enrollment-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Published December 12, 2017. Accessed September 24, 2020.

9. Rosenbaum S. Medicaid Payments and Access to Care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371(25):2345-2347. doi:10.1056/nejmp1412488

10. Two-Thirds Of Primary Care Physicians Accepted New Medicaid Patients In 2011–12: A Baseline To Measure Future Acceptance Rates | Health Affairs. Health Affairs. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0361?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%20%200pubmed. Published 2011. Accessed September 24, 2020.

-

College

AAC

-

Zoom

https://us04web.zoom.us/j/6966232478?pwd=eEhXZkJ4Y3d5dDZiY20yNWQyR1VYUT09

-

PDF