-

Author

Benjamin Kartub -

Co-author

-

Title

Thigh silicone granuloma after silicone injection for gluteal augmentatio

-

Abstract

Purpose:

To describe a case of granuloma formation after free silicon injections that had migrated from the posterior buttock to the anterior thigh.

Background:

Soft-tissue augmentation and cosmetic surgeries or procedures come in many different varieties, from implant-based augmentation to fat injections to injectable fillers. While these procedures have their risks and benefits, they are all researched, well-regulated, practiced by trained physicians. However, due to lower cost and lack of knowledge of the risks, there is arising a more and more common trend for patients to seek out similar augmentation procedures from illicit sources: namely non-physicians providing injections of unknown substances in homes, basements, and hotel rooms. Often silicone is the material of choice for these illicit injections. And while silicone, even medical grade silicone, seems safe based on its widely recognized association with cosmetic surgery, these non-FDA approved injections are very different from the implant-based procedures they may be masquerading as.

Free silicone is not encapsulated as it is in implants. This leads to two problems. The first is that, when it is not encased, free silicone can and does migrate. Many case reports detail local migration around the head and neck for facial implants, or around the thigh, leg, or pelvic region for gluteal augmentation. These deposits of injected silicone eventually spread as large discrete masses, as small, dispersed particles, or as thin tendrils which migrating more diffusely. The second problem that arises from the lack of a barrier between the silicone particles, now broadly dispersed, and normal tissue is that a foreign body reaction, a type-four hypersensitivity reaction to the silicone, ensues and causes granuloma formation. Unable to break down the very stable silicone molecules, macrophages recruit fibroblasts which create a fibrous capsule to wall off the foreign material, resulting in a hard nodule or granuloma. Granuloma formation is a common adverse effect of these procedures, with estimates ranging from 1 to 20%. These granulomas occur sometimes many years after the injections themselves, and the trigger for their formation is not understood. Regardless, the inflammation causes the nodules to become painful and the aesthetic impact can be severe depending on the location and amount of migration, as well as the extent of granuloma formation. Secondary infection of these granulomas is not uncommonly described in case reports.

Treatment of these silicone granulomas is complicated. Due to the migratory nature, where many small particles are broadly dispersed over a large area, surgical resection is often not possible. Such surgical attempts at removal could not remove every silicone nodule; even if they could all be successfully identified the procedure would lead to significant disfiguration. Surgery is limited to large areas of active inflammation which, though effective when conditions are right, still leaves the possibility of recurrence at another site of migration later on. Non-surgical treatments are available and are centered around limiting the inflammatory response. Options include intralesional steroid injections such as triamcinolone or betamethasone, which are similarly limited to large nodules, or systemic immune-modulating agents such as 5-fluorouracil and TNF-alpha inhibitors. While some have reported good outcomes with steroid injections, general consensus remains that results are uncertain. Systemic therapies are newer and, while promising, are not yet well studied and as a result not widely practiced by providers.

Case Description:

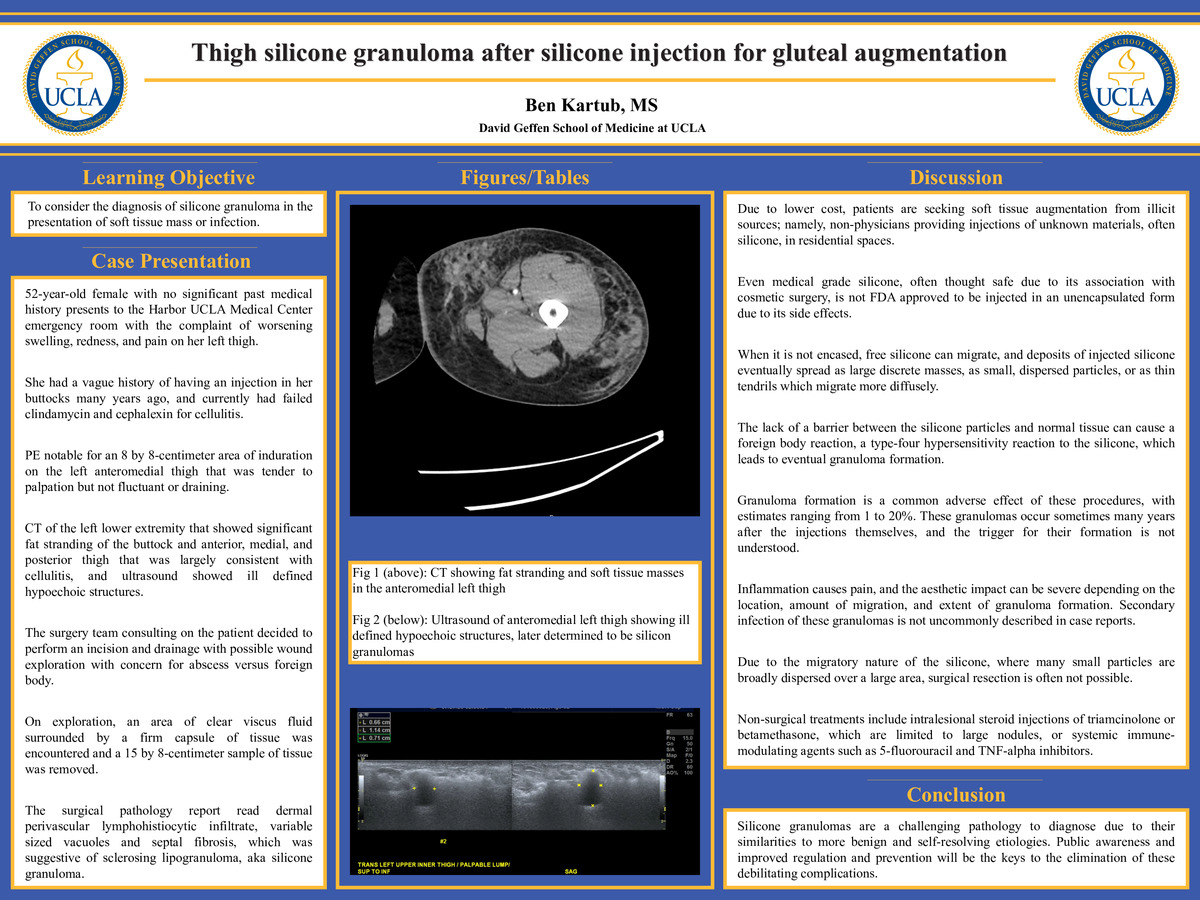

The patient is a 52-year-old female with no significant past medical history who presented to the Harbor UCLA Medical Center emergency room with the complaint of an area of worsening swelling, redness, and pain on her left thigh. Her symptoms had been present for two months, and at the beginning of her course she was seen by her primary care provider who prescribed clindamycin for cellulitis. Her symptoms continued to progress, and she subsequently failed a trial of cephalexin, at which point she was advised to seek a higher level of care. Notably, the patient endorsed having a similar infection in the same spot around three years ago that responded to antibiotics, and she reported a vague history of having an injection in her buttocks many years ago. In the emergency room, the patient’s exam was notable for an otherwise well appearing female with a large, 8 by 8-centimeter area of induration on the left anteromedial thigh that was tender to palpation but not fluctuant or draining and a larger warm, tender, and erythematous patch encompassing the induration as well as the majority of her medial thigh. Vital signs, including temperature, and laboratory values were within normal limits. The patient received a CT of the left lower extremity that showed significant fat stranding of the buttock and anterior, medial, and posterior thigh that was largely consistent with cellulitis. The patient underwent a period of observation and IV vancomycin, with her ensuing clinical course notable for an elevated ESR (50 mm/hr) and CRP (2.82 mg/dL) and an ultrasound that showed ill defined hypoechoic structures correlating with the area of swelling that were suggested to possibly be a result of taenia solium infection. At this point, the surgery team consulting on the patient decided to perform an incision and drainage with possible wound exploration with concern for abscess versus foreign body. On exploration, an area of clear viscus fluid surrounded by a firm capsule of tissue was encountered and a 15 by 8-centimeter sample of tissue was removed. The surgical pathology report read dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, fat necrosis, focal lymphocytic aggregates, variable sized vacuoles and septal fibrosis, which was suggestive of sclerosing lipogranuloma. The patient’s wound cultures were negative, and she had an uneventful post-operative course. While she recovered appropriately by her clinic follow-up appointments, she did endorse similar pains in other sites in the buttock and thigh from the same injections. She was eventually lost to follow-up due to moving out of state.

Conclusion:

With broader social acceptance, soft tissue augmentation and cosmetic procedures as a whole are becoming more common. Low cost, lack of knowledge of the risks, and difficulties in legal regulation have caused a significant portion of this increase to be in the form of illicit injections, often of free silicone. The resulting migration and granuloma formation leads to pain, disfigurement, and a protracted clinical course with no guaranteed satisfactory resolution. The patient presented in this case report represents the risk posed to this population, in that they have a difficult time arriving at their final diagnosis because of the newness of this problem and the tendency of a silicone granuloma to be masked by simple cellulitis. A high degree of clinical suspicion is necessary to seek the proper diagnostic work-up. Her initial CT scan made no mention of her probable silicone nodules until the patient was reassessed, an ultrasound performed, and the history and ultrasound correlated with the CT images. Unfortunately, even if these patients are correctly diagnosed and treated, their long-term course is uncertain. Systemic or preventative treatments will need to be better studied, lest patients like this go through this whole process cyclically as new nodules become inflamed at different times. Ultimately, better public understanding of the risks involved in these procedures, hopefully leading to their elimination, will be the only truly effective way of curtailing the debilitating adverse reactions.

-

College

AAC

-

Zoom

-

PDF